Design

Dogtown Reborn

Vintage wall signs have been restored in this St. Louis neighborhood.

Published

17 years agoon

Two vintage wall signs have been vividly restored in a central St. Louis neighborhood known as Dogtown. The collaborative effort paired the Dogtown Historical Society with legendary signpainter Lonnie Tettaton, the city’s only working walldog.

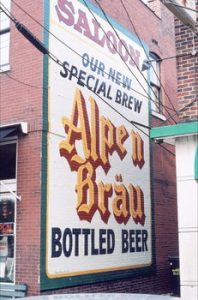

The first sign, a large ad for Alpen Brau Beer, adorned the south wall of D.T. Coyne’s Saloon a century ago. Located at the Tamm and Clayton intersection, in the heart of Dogtown, the sign probably was painted in 1904, just prior to the World’s Fair. The event (also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition) coincided with the 1904 Summer Olympics. It rated as the biggest extravaganza this country had ever seen and was held in spacious, nearby Forest Park.

Situated in a narrow gangway, the sign has been fairly well-protected from sunlight and elements for most of the 20th Century, but, originally, it broadcast the Alpen Brau brand name to pedestrians several blocks away.

“At the time this sign was painted, there were no buildings between it and West Park, two blocks down, where the trolley cars stopped,” said Bob Corbett, treasurer and founding member of the Dogtown Historical Society (DHS). “The entrance to the Fair was three blocks north of the saloon, so people getting off the trolleys and walking to the Fair could see the sign from a distance.”

The lager-style Alpen Brau was produced by the Columbia Brewing Co., which operated in St. Louis from 1892 to 1948, when it sold out to Falstaff Brewing. The Alpen Brau brand, introduced at the 1904 World’s Fair, marketed its slogan, “nothing finer in a bottle.”

AdvertisementCorbett said he first proposed restoring the advertisement in May 2002, following a second DHS meeting. “I said I would like everybody to walk with me up the street for 10 minutes. I showed them the sign and said, ‘This is what I want to do as a project.’ They said, ‘Great! How do we do it?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’”

Nearly four and a half years later, the wall sign finally received its makeover.

“We had to get permission from the various city authorities, permission to paint it and permission to move electrical wires. We had to get permission from the building’s owner, and we had to raise money. But the biggest obstacle,” said Corbett, “was finding someone to paint it.” Eventually, through word of mouth, they found the perfect person.

Tettaton, 72, has been painting St. Louis wall signs, large and small, simple and complex, for more than 50 years. Besides having the contract to maintain the massive Switzer’s Licorice wall sign located near the riverfront, Tettaton recently created a highly visible wall sign along I-55 South for the Lemp Mansion Restaurant. Conceived by Tettaton and Lemp Mansion owner Paul Pointer, the sizeable ad depicts an old-time bartender pouring a beer. It looks and feels like an early 20th-century advertisement.

These days, Tettaton walks with two canes, having fallen off a ladder during a job five years ago. Although the accident broke his heels and ankles, and left him with surgically implanted pins in his legs, he can still get up on a ladder with a brush and paint can.

AdvertisementTettaton started tracing the original Alpen Brau beer ghost sign during a beautiful week in September 2006. Assisting him was Charlie, “a halfway homeless guy.” Lonnie and Charlie didn’t work in solitude. Their efforts attracted a gaggle of onlookers throughout the project, including neighbors with cameras and reporters with pencil and notebooks.

“It was a big thing there,” Tettaton said. “Everybody was behind it. I never saw a community that was so enthusiastic about an old wall sign. People who’re born and raised here, their families have been around for generations; they feel this is something worth doing. To them, it’s not a faded-out wall; it’s a work of art from the past.”

In contrast, Tettaton noted how certain heritage-conservancy groups opposed restoration of a handsome Bull Durham wall in nearby Collinsville, IL. Despite protests, the bull has been restored. Similarly, Tettaton could cite simple public apathy over some wall-sign preservation.

In June 2007, during urban-renewal-triggered demolition, a beautiful red, gold and blue Gold Medal Flour sign became exposed on a red, brick building. Yet one week later, the building was razed. Such is life.

The Alpen Brau sign actually comprised two separate signs, one painted over the other. This commercial double-exposure, with portions of text jumbled up, required research about the more prominent ad. Thus, the Corbetts — Bob and his brother, DHS president John — and Henry Herbst, another DHS member, scoured the St. Louis Public Library and the Missouri Historical Society for archived references.

Advertisement“They got old pictures and labels,” Tettaton said. “They did the homework, and we were able to get something that looked authentic.”

But faithful restoration could only go so far. Ironically, lead paint, which is the reason the sign still exists, no longer legally exists. Outlawed since the ’60s, that paint al’lowed the pigments to actually soak into the brick. For the restoration, ready-mixed bulletin enamel would have to do.

“They pretty well made their own paints back then,” said the knowledgeable Tettaton. “They mixed in their oils and pigments. I think they started selling paint in cans in the 1920s. Devo was one of the first companies to do that.”

Nonetheless, the bulletin enamel, more suitable for billboards than brick walls, should be fairly durable.

“It’ll probably be there 30 years from now, maybe more,” Tettaton said, adding with a wink, “longer than I’ll be around.”

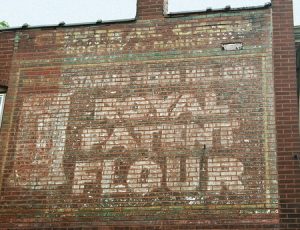

Approximately 10 months after the Alpen Brau project, the DHS lined up Tettaton to restore another old sign, six blocks to the west. This Royal Patent Flour ad had adorned the west wall of a corner grocery. While the Alpen Brau sign’s biggest obstacle was finding a signpainter, they now needed to find this building’s owner. Armed with eventual permission, the project galloped ahead.

Within days, Tettaton and his helper, Bill Fishback, perched atop a rented, hydraulic-lift platform, painted away, giving the sign its first physical attention since World War I. The Alpen Brau sign required seven days’ labor at a price of $2,000. Tettaton received $1,600 for the three-day Royal Patent project.

As with the Alpen Brau brand, Royal Patent flour, made locally by the Stanard-Tilton Mill, also required research. The words “Royal Patent Flour” were legible enough, but the rest of the ad copy was only partially legible. Off to one side, the illustration (a sack of flour) and text barely provided an outline.

In the cavernous Missouri Historical Society library, Bob Corbett and fellow DHS member Sally Sharamitaro pored over a 1918 St. Louis City Directory. Having found the address in question, they saw the building had been the Central Cash Grocery & Market. Now they had ad copy for the signs’ upper portion. But what about the flour-sack lettering?

“I was doing something else,” recalled Bob Corbett, “and Sally kept on looking through the directory. Suddenly, she said, ‘Well, what do you know!’” The full-page ad she’d found for Royal Patent Flour not only showed the larger ad copy’s arrangement, but also the flour sack’s minute lettering.

Interesting, too, Tettaton noted, both wall signs carried the same double border — green stripe on the outside, yellow stripe on the inside. He surmised the same company painted both signs.

Bob Corbett admits his interest is more local history than signage. “We wanted to do something in the public arena to bring Dogtown history back to the people,” he said. “These signs remind us of the role of the local tavern and the corner market, both essential to a thriving community,” adding, the DHS also plans to mount plaques on the sign sites “to commemorate the role of these businesses. I just wish we had more historic wall signs to restore.”

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

6 Sports Venue Signs Deserving a Standing Ovation

Hiring Practices and Roles for Women in Sign Companies

Avery Dennison Adopts Mimaki Printer for Traffic Sign Print System

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Signs of the Times magazine's news bulletin.

Most Popular

-

Tip Sheet3 days ago

Tip Sheet3 days agoAlways Brand Yourself and Wear Fewer Hats — Two of April’s Sign Tips

-

Business Management1 week ago

Business Management1 week agoWhen Should Sign Companies Hire Salespeople or Fire Customers?

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs Award Winners Excel in Diverse Roles

-

Real Deal4 days ago

Real Deal4 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Editor's Note1 week ago

Editor's Note1 week agoWhy We Still Need the Women in Signs Award

-

Line Time2 weeks ago

Line Time2 weeks agoOne Less Thing to Do for Sign Customers

-

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week agoADA Signs and More Uses for Engraving Machines

-

Women in Signs4 days ago

Women in Signs4 days ago2024 Women in Signs: Megan Bradley