Perhaps the best way to describe the fleet-graphics market is "burgeoning." But is this market something you want to tap? If you already have a mid- to large-format digital printer, the answer may be yes. To help decide, we asked a couple of digital sign-printing bureaus — ICON Digital Productions Inc., Markham, Ontario, and Colorquest Graphics, Joppa, Md. — what they think about this digital-printing niche. Here’s what they had to say:

ICON has been in the digital-imaging business for 2 and 1/2 years, and uses a Xerox electrostatic printer and Xerox PrintMarX films. According to Vice-President Peter Evans, fleet graphics account for about 20 percent of ICON’s business. He says, "Fleet graphics have become more popular over the years as printing technology and materials have continued to improve." He adds that many companies with smaller fleets cannot justify the cost of screen-printed graphics for their vehicles. By using digitally printed graphics, they can maximize advertising impact by keeping their fleet messages fresh.

Steve Venick, marketing manager at Colorquest, says about 50 percent of his company’s digital output is devoted to fleet graphics. In business since 1994, he says Colorquest’s biggest challenge is keeping up with the competition. Venick notes, "I think there’s enough (business) out there, it’s just a matter of finding it."

So how does a digital-service bureau find companies that need fleet graphics? One tool Venick finds helpful is a trucking directory, listing all the owners of fleets. From there, it’s simply a matter of calling the companies and convincing them that they need graphics on their trucks. Another way is to attend trucking shows. According to Venick, many trucking conventions are held every year, and Colorquest tries to pick the "right ones" to attend and drum up new business.

Evans says ICON employs a team of salespeople who target "companies that sell products that enjoy mass appeal." He adds, "Consumer-product companies that aim to reach the masses in their advertising campaigns are key prospects for fleet graphics. [However], it’s also important that they have a fleet of vehicles." According to Evans, it’s important to sell the idea to the advertising managers within companies and prove to them that they can get more value from a fleet-graphics program than by spending money on other media.

But with the proliferation of digital service bureaus, competition is stiff. Venick says, "Customers are price-shopping and basically looking [only] at dollars. We’ve been outbid probably more times than not." He adds that one way his company is trying to stay competitive is by adding another, faster printer that will also make production more cost-effective. Colorquest currently employs 3M’s Scotchprint 9512 and is looking into buying the Scotchprinter 2000. And Venick says although some self-adhesive vinyls are durable, they’re expensive, which is another challenge the company faces in dealing with customers who are reluctant to pay for these graphics.

Evans agrees that the market is competitive but adds, "Fleet graphics is a market that most digital printers jump at because of the sheer square footage of the sales. However, like any other product or market, it’s not just a matter of being able to produce, but being able to produce well." To keep its head above water, ICON sticks by the old rule: Do a good job, charge a fair price, and the customers will come and stay with you. Says Evans, "We take a lot of pride in the fleet graphics we produce. We have to — we see our work every day!"

So, what’s the future of fleet graphics? Venick says the fleet-graphics industry will continue to grow, and more and more companies will realize the benefits of fleet graphics. But he feels that competition will make it difficult for digital printers to turn a profit. As such, he says it’s always good to diversify into other markets. And although Colorquest is not currently involved with the newly emerging "mobile-billboard industry," he says he thinks it’s "a great idea, and we’re looking into it."

Evans, on the other hand, is not embracing the mobile-billboard concept of flexible-face billboards on trucks. He says, "Maybe I’m biased, but I have yet to see a flex-face mobile billboard that looks as good as a well-installed, pressure-sensitive fleet graphic." He thinks that major improvements need to be made for a flexible-face system to effectively compete with self-adhesive vinyls.

Taking Fleet Graphics to New Heights

Digital printing may be the fastest way to output full-color, changeable images. But what about a fleet that spends most of its time with its head — er, tailfins — in the clouds?

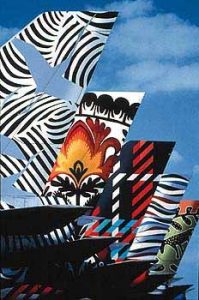

Last year, British Airways began repainting its fleet of 350 planes as part of its new corporate identity. Rather than being viewed as an airline flying to and from Britain, it wants to be seen as an airline that serves the world. As part of its makeover, its fleet of planes are being repainted gradually, over a three-year period, and the name "British Airways" is being printed in a softer, rounder typeface using a lighter, brighter palette of red, white and blue, to reflect the British Union flag.

In addition to the new logo colors, the planes’ tailfins are being painted with different designs created by artists all over the world. To date, 115 planes have been painted using 50 world images. In a massive art commission, a London-based design consultancy team searched for famous and obscure artists in different countries. They selected a variety of painters, ceramicists, potters, weavers, quilt-makers, calligraphers, flag-makers and sculptors, and commissioned them to design patterns that reflect their native country’s identity.

On June 10, 1997, 15 world images were unveiled, and 12 world images are planned to be added each year until the millenium. All of the planes are painted using heavy-duty, industrial paint that provides essential protection for the aircraft against corrosion, hydraulic- and de-icing fuel, the weather and powerful UV rays in higher atmospheres. The environmentally friendly paint has low amounts of solvents and paint additives that could harm the ozone layer. Each tailfin image is applied with layer upon layer of stencil, using a range of colors. It takes takes four days and 560 man-hours to paint the entire plane. The average paint life of an aircraft is at least five years.

Here are some of the designs used on the planes and who made them:

- Union Flag — a version of the British Union Flag, designed by the Historic Dockyard, Chatham, United Kingdom.

- Ndebele — murals in flat panels of bright colors and dynamic geometric patterns seen in houses of the Ndebele people of Mpulmanga in eastern South Africa, designed by Emmly and Martha Masanabo.

- Nami Tsuru — a symbolic painting of waves and cranes from Kayama Matazo, one of Japan’s leading artists.

- Benyhone — a Scottish tartan called Mountain of Birds was designed by weaver Peter MacDonald, and incorporates ancient Highland techniques, patterns and colors.

- Sterntaler — a Bauhaus-inspired geometric ceramic panel from German artist Antje Bruggemann.

- Delftblue Daybreak — inspired by the traditional motifs of blue and white Delft ceramics, created by Hugo Kaagman, who began work as a graffiti artist in Amersterdam’s city center.

Tip Sheet1 week ago

Tip Sheet1 week ago

Ask Signs of the Times2 days ago

Ask Signs of the Times2 days ago

Real Deal1 week ago

Real Deal1 week ago

Benchmarks5 days ago

Benchmarks5 days ago

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology2 weeks ago

Product Buying + Technology2 weeks ago

Photo Gallery7 days ago

Photo Gallery7 days ago