"The best prophet of the future is the past." — John Sherman, 1890

From the timeworn pages of Signs of the Times’ earliest editions (1906-1912) emerges a rich and remarkable profile of the electric-sign industry’s beginnings. Influenced by our millennial compulsion to compare past and present, I recently investigated the state of the sign industry during the early years of the twentieth century.

Despite vast differences in technology, I was struck by the similarity between subjects discussed a century ago and our current topics. I also gained considerable appreciation for our predecessors’ common sense. Without this historical record, people can easily idealize the past and assume that today’s challenges are unparalleled. Thus, sign professionals and industry analysts sometimes condemn current trends without realizing that a previous generation of signmakers once traveled the same roads.

Signs of a new age

America’s Industrial Revolution laid the groundwork for an explosion in demand for advertising signs during the period 1875-1900. Mass marketing of consumer goods began when the nation’s first large department stores opened in several major cities. Prior to this time, people purchased necessities in cluttered dry-goods stores where merchants were unacquainted with modern concepts of advertising, merchandising and customer service.

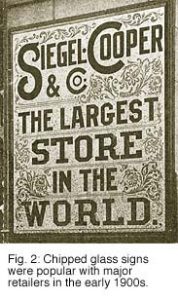

Philadelphia merchant John Wanamaker changed the status quo when he purchased and remodeled the abandoned Pennsylvania Freight Station on Market Street (Fig. 1). Opened in 1876, Wanamaker’s cavernous Grand Depot store was the nation’s first retail department store. Other department store pioneers included Marshall Field, who opened his first Chicago store in 1881, and Henry Siegel, who teamed with Dutch-born Frank Cooper to open Chicago’s Siegel-Cooper store in 1887 (Fig. 2).

During the period from 1900-1915, department store construction boomed, as retail stores like Marshall Fields, Carson Pirie Scott, Macy’s, Altman’s, Lord & Taylor, Stern’s, Saks, Filene’s, Famous-Barr, Bloomingdale’s and Lazarus gained strong positions in a burgeoning consumer market. These stores dramatically changed the ways that consumer goods were sold. Advertising, merchandising and marketing suddenly became essential to the survival of every retail business, regardless of its size or product line.

But traditional values initially formed roadblocks. Before 1890, for example, visual merchandising was identified with snake-oil salesmen and circus trickery. Thus, the merchants who opened America’s first department stores needed to invoke powerful devices to gain public acceptance for the new material culture.

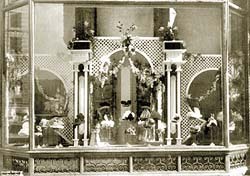

Show windows were introduced to meet this need (Fig. 3) and soon became an early version of TV advertising. Because most people in those days considered staring into windows to be rude, merchants left nothing to chance. To encourage gawking, department stores hired well-dressed, professional "window gazers" to stand outside stores and arouse curiosity by staring into the show windows.

Many religious and community leaders condemned these retail "peep shows." Writing in the winter of 1911 after her first encounter with a Chicago show window, novelist Edna Ferber scolded, "It is a work of art, that window, a breeder of anarchism, a destroyer of contentment, a second feast of Tantalus. It boasts peaches, downy and golden, when peaches have no right to be. Strawberries glow therein when shortcake is a last summer’s memory."

Public Decency

Early critics of consumer advertising also were concerned about its impact on standards of public decency. In Spokane, WA, for example, when a department store first displayed female mannequins attired in revealing evening gowns, police were called in to break up a crowd that had jammed in front of the show window.

In 1897, L. Frank Baum, author of The Wizard of Oz, published the first issue of The Show Window, a forerunner of ST Publications‘ VM+SD magazine. In addition to authoring many popular children’s books, Baum was a visual-merchandising pioneer. His monthly journal provided instruction and design ideas for show-window designers. In 1898, Baum founded a trade organization, the National Assn. of Window Trimmers.

Some things never change

Even in the earliest days of electric signs, industry leaders were concerned about professional standards. For example, in ST‘s May 1908 issue, Gerald B. Wadsworth, president of the New York Adv. League observed, "The majority of advertising men today are about as competent in their trade as the medicine men of old were in protecting the lives of their patients. While the medical and legal professions demand extensive training and certification, the only requirement for becoming an advertising man is the ability to present your victim with a good line of talk."

Numerous columns and subscriber letters published in ST during these early years echoed Wadsworth’s point of view. Sign professionals of that time were equally concerned about dishonest sales practices, price chiseling, design/artwork theft and fly-by-night competitors.

ST‘s December 1907 issue describes how a slippery salesman swindled Philadelphia signmaker Julius Ebner. A young man offered to sell Ebner’s signs on a "straight commission" basis. Ebner agreed and provided the salesman with a set of 12 oilcloth sign samples.

Two days later, Ebner received a purchase order from a local merchant ordering "a dozen more" signs at a price of 10 cents each. Because his price was actually 50 cents for each sign, Ebner immediately went to the merchant’s place of business to investigate. When he walked into the merchant’s shop, Ebner noticed all his samples neatly displayed on the walls. The missing salesman had pocketed 10 cents for each sample and told the merchant to order additional signs from Ebner at the same price.

Ye Olde Sign Code

If you believe sign regulations started with FDR and the New Deal, think again. When demand for signage initially exploded during the 1890s, no regulations existed to control sign and billboard construction. As a result, signs commonly collapsed because of improper design, engineering and installation. Many unqualified people were constructing electric signs, and sign-related fires destroyed buildings in several cities. Does this situation sound familiar?

City authorities responded by adopting sign ordinances, some of which were quite restrictive. In response, coalitions of outdoor advertisers and merchants successfully fought these codes in court. Many of these legal challenges were upheld, and sign regulations were struck down in several cities. Transcripts of legal rulings from this period can inspire those who face unreasonable sign codes today.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, ST reported many examples of aggressive municipal sign regulation. In 1906, the city council of Poughkeepsie, NY, voted to compel removal of all swinging signs, because they forced pedestrians to walk into the street to locate shops.

In 1907, a court ruling in New York City banned large signs attached to sides of omnibus vehicles traveling along Fifth Ave. The omnibus companies sued to prevent this regulation, but the judge ruled in the city’s favor. When we contemplate the huge number of vinyl bus wraps and other large-format vehicle graphics today, this century-old ruling seems draconian. In any case, historical records dispel the notion that signmakers of yesteryear were free to do as they pleased.

The Borough of Brooklyn, NY, enacted its first electric-sign ordinance in 1907. Other big-city sign codes enacted during this period conformed to a basic regulatory model that specified the following requirements:

Tip Sheet1 week ago

Tip Sheet1 week ago

Ask Signs of the Times2 days ago

Ask Signs of the Times2 days ago

Real Deal1 week ago

Real Deal1 week ago

Benchmarks4 days ago

Benchmarks4 days ago

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Editor's Note2 weeks ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology2 weeks ago

Product Buying + Technology2 weeks ago

Photo Gallery6 days ago

Photo Gallery6 days ago