Metal Fabrication

Jersey Works

Design Works successfully incorporates trends and tradition.

Published

17 years agoon

Larry Plummer, proprietor of Hillsborough, NJ-based Design Works, has lived the all-American signmaker's career. He envisioned a graphic-design career during his schooling, paid his dues at a large sign company, formed a partnership and, ultimately, set out on his own.

Having worked in New Jersey throughout his career, Plummer has exploited the Garden State's unique melange of rustic, tranquil communities and bustling, urban locales to create a diverse signage repertoire.

Plummer's consistently strong body of work shouldn't be confused with the miraculous turnaround Coach Greg Schiano orchestrated with the Rutgers University football team (the pride of Piscataway) this past season. However, it underscores that, like many aspects of commerce and culture, New Jersey's signage is underrated, and his portfolio is a prime example.

Sign education

While studying art at Mercer County College (West Windsor, NJ), Plummer picked up an airbrush and immediately become enamored of its artistic potential. He began his career in the mid-1970s, when vans were the hip recreational vehicle. He capitalized by rendering murals on Chevy Vanduras, Ford Econolines and other era sin bins. Plummer emulated the era's popular airbrush artists, such as Frank Frazetta and Boris Valejo, who created vivid scenes of mythical and medieval warriors and creatures.

AdvertisementHowever, as the fad passed, Plummer recognized the need to broaden his skills, and he took a job at Bordentown, NJ-based State Sign Co. There, under proprietor Joe Sharp's tutelage, Plummer learned the finer points of handcarving dimensional signage, channel-letter fabrication, electric-sign service, screenprinting and vehicle lettering.

"Joe was a great old-time sign guy," he recalled. "He was very hardworking and knowledgeable, and a patient, thorough teacher. I learned the industry from top to bottom, which helped me determine my career's direction."

In 1982, he started Design Works in Trenton. For the next 10 years, he filled his growing portfolio with painted and dimensional signs, as well as vehicle lettering and graphics. When new gubernatorial administrations and other state-government officeholders set up shop in Trenton, Plummer was often called to change the gilded names on state-capitol doors.

In 1992, he and his then-assistant, Kim Arena, partnered with Richard Rutzler, another local signmaker, and founded Future Signs in Trenton. The company initially emphasized sandblasted and screenprinted signage, but eventually fabricated channel letters, sign cabinets and other electric signs. To handle more extensive wiring and installation, the company grew to eight employees. Thus, Plummer's job description changed, which compelled him to redirect his career once again.

"With a shop that grew to that size, I spent a lot of my time dealing with such administrative issues as supervising my staff and chasing down permits," he said. "My work became less centered on the artistic side of the sign business, and I no longer enjoyed my job as much."

In 2000, Plummer sold out his share in Future Signs and moved with his wife, Mary Ann, to Hillsborough, which neighbors Princeton and its idyllic, Ivy League setting. He reincarnated his company as Design Works Custom Studio LLC, and Plummer is happy to work in a two-person production area again. Eric Sieberg handles painting, fabrication and installation (Mary Ann handles the bookkeeping).

AdvertisementThough he possesses ample experience lettering and pinstriping cars, Plummer defers such jobs to other New Jersey shop owners. He said, "There are so many great car guys around here, like Rich Domby, Julian [Mr. J] Braet and Alan Johnson; they're tough to compete against," he said. He devotes his core business to dimensional, routed or handcarved signage.

"I've made that my specialty, and I find it to be very rewarding work," Plummer said.

A successful formula

A revitalization — New Jersey's smaller, industrial cities adapting to modern economic realities — has bolstered his bottom line. As civic leaders entice service-related businesses, they ask signmakers to develop wayfinding and cityscape signage that helps give communties more personality.

"These local governments are receiving state and federal grant money to develop their 'Main Street' business districts to create gateway signage and civic wayfinding," he said. "I attended a tradeshow for the New Jersey League of Municipalities, and I encountered a tremendous demand for signage upgrades."

AdvertisementWhen dealing with civic sign programs, Plummer said it's important to be reasonable and specific with your pricing because the customers usually have tight budgets and need explicit detail to address monetary layouts. And, get in on the ground floor by creating designs.

"Make sure you get them copyrighted, so you still get paid even if they take your design and choose another fabricator."

He fabricated one such program for South Bound Brook, a borough with approximately 5,000 residents within Somerset County, in north-central New Jersey. The township's chamber of commerce, zoning board and engineer established guidelines and regulations.

Plummer first developed the borough's entry sign, a routed, dimensional panel installed on a keystone wall at the town's city limits. Subsequently, he developed monument signage for the city's municipal building and a pedestrian-oriented, freestanding directory downtown that indicates where to find local merchants. Plummer also fabricates horse-farm and church signage, although demand has recently diminished.

The tools and talent

Plummer handles virtually all work inhouse. He said, "I just can't let any part of a project out of my sight. I do my installations because I think of my signs like children I'm sending off to college."

His most beloved tool is his Techno Isel LC 48 x 96-in. router. Though a skilled signcarver, Plummer appreciates the machine's efficiency and precision. If he prefers a well-defined texture for a specific job, he turns to his inhouse sandblasting apparatus. "Sandblasting is a rough, dirty job, so it's important a shop uses a high-powered compressor," Plummer said.

In addition to routing Sign*Foam¨ HDU panels (he tends to choose 1.5-in.-thick, 15-lb. material because it's less expensive than stouter varieties), he machines copious amounts of composite material, such as Alumalite or Dibond, to provide an appearance of added dimension. He's experimented with latex paints and lettering enamels, such as 1Shot, but he's partial to the luster and durability of acrylic polyurethanes. He also decorates many of his signs with 23k surface leaf, which he prefers to patent leaf, because it's more lustrous and applies easily.

Plummer continued, "There are a lot of jobs with tight deadlines that I have to turn around quickly. But, when time allows, I like to use slow size before applying goldleaf, and let it cure for up to 24 hours before laying on the gold. This provides a rich burnish that really adds to the finished product."

For one novel project, he developed a roadside sign for Dragonfly Farms, a garden center and nursery a few miles outside Hillsborough. Because the sign required fine detail, he handcarved an oval panel with a dragonfly inset, with chisels for broad shaping and wire brushes for intricate definition.

To create the logo, Plummer hand-sketched a dragonfly before scanning it into SignLab, to create a digital template to fashion the router-cut components. Because the client wanted a distressed look, Plummer decorated the panel with copper leaf and left it to weather and patina in the shop for approximately two months. When the customer finally called for its installation, he applied several clearcoat layers to temper the weathered effect.

Plummer plies most of his trade in small towns, and his hard work has earned him positive word of mouth that wins repeated business and spreads his reputation to proximate cities in need of a graphic makeover (his website, www.designworkssigns.com, attracted a would-be customer from Wyoming, but the trek would have incurred too many expenses).

All things considered, he's evidently found his niche.

"I know a signshop can't only take the projects it wants," Plummer said. "But, I've put myself in a position where I can be a bit selective. I really don't want to grow my shop or my staff, except maybe to hire a part-time bookkeeper or designer.

"This is a great job — where else can you get your hands dirty, experiment with new materials or ideas, and get paid for it?"

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

Advertisement

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Signsofthetimes Magazine.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Tip Sheet4 days ago

Tip Sheet4 days agoAlways Brand Yourself and Wear Fewer Hats — Two of April’s Sign Tips

-

Business Management2 weeks ago

Business Management2 weeks agoWhen Should Sign Companies Hire Salespeople or Fire Customers?

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs Award Winners Excel in Diverse Roles

-

Real Deal5 days ago

Real Deal5 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Benchmarks20 hours ago

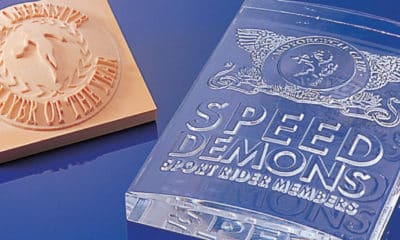

Benchmarks20 hours ago6 Sports Venue Signs Deserving a Standing Ovation

-

Editor's Note1 week ago

Editor's Note1 week agoWhy We Still Need the Women in Signs Award

-

Line Time2 weeks ago

Line Time2 weeks agoOne Less Thing to Do for Sign Customers

-

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week agoADA Signs and More Uses for Engraving Machines