Electric Signs

Resurrecting the Legends

Museum signage for jazz, baseball greats

Published

18 years agoon

During the turn of the century, Kansas City, MO, became the cradle of a new music known as jazz. Freed slaves journeying north along the Missouri River imported the rhythmic music of their native Africa. This aesthetic, mixed with European-style orchestral instruments, yielded a new, improvisational music in which melodies jumped, rhythm sections hopped and brass instruments wailed. Jazz, according to many cultural critics, became America’s first and greatest indigenous art form.

By the 1920s, jazz was the signature time in which Kansas City moved. The wide-open city boasted dozens of clubs, centered mostly around 18th and Vine streets, where music and booze perpetually flowed. This vibrant atmosphere earned Kansas City the nickname "Paris of the Plains." Some of its native sons, namely Charlie "Bird" Parker and Big Joe Turner, fed on this spark and went on to worldwide fame. Other notable figures of the era, such as bandleader Count Basie, adopted KC as their hometown. And everyone who was anyone in the jazz world knew the city inside and out.

Though best known as a musical epicenter, the 18th and Vine neighborhood also served as the civic and municipal heart of Kansas City’s black community. In a city still drawn along segregated lines, the district offered black citizens a place to eat, do business and socialize. Soon, another cultural attraction came to town. Before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, black players were forced to form the Negro Leagues, a constellation of teams spread through the big cities of the east and midwest. Kansas City’s club, the Monarchs, featured such stars as Satchel Paige and Buck O’Neil.

By the 1950s and 60s, however, the area around 18th and Vine began to change. Musical styles shifted, Jackie Robinson had made the Monarchs obsolete, and integration allowed blacks more mobility. Slowly but surely, the district fell into disrepair. By the 1980s, a few clubs and restaurants stood as little more than reminders of a time long gone.

Today, however, that legendary past is showing new signs of life. The Museums at 18th and Vine, a $26 million dollar, 55,000-square-foot complex that pays homage to both jazz and baseball, has come to fruition. Since opening the doors in September 1997 to enthusiastic crowds, the Museums at 18th and Vine have served as a crossroads of the past, present and future.

Signs of life

As with any architectural project, the exterior design set the project’s entire tone. Kansas City architects Gould Evans Goodman re-created the brick storefront appearance of the old urban district. The only remaining building on the site was a defunct jazz club, the El Capitan. This two-story brick and woodframe structure was rehabbed to house part of the jazz museum. The materials inherent in the old club were used to anchor the entire space.

To establish the look and feel of the place, Gould Evans Goodman hired Kiku Obata & Co., based in St. Louis, to design exterior environmental graphics and signage for the Jazz Museum, a nightclub and a gift shop. "The signage we developed is reminiscent of the time when 18th and Vine was in its heyday," says Chris Mueller, project designer.

According to Mueller, Kiku Obata designers decided to incorporate human figures into the main-identification signage to express the idea of a thriving neighborhood. They had already been given a specific space to fill because Gould Evans Goodman used a brick proscenium archway for the entrance. "The proscenium was an atypical feature," says Mueller. "It was a challenge because it created strange spaces. We decided that we would use illustrations and create people as signage."

The company contracted with Alex Sacui, a young illustrator who brought to the table a good grasp of the human face and figure. Sacui created seven figures: baseball players on each end, an elderly man with cane and hat, a female blues singer, a newsboy selling copies of the Kansas City Call, a young girl waving a KC banner, and finally, a saxophone-playing figure inspired by Charlie Parker, the city’s most famous, and most tragic, native son.

Once the designs were complete, Lawrence, KS-based Star Signs took on the fabrication. The seven entryway figures were transferred onto 1/8-inch porcelain enamel. To keep the images bright and vivid after dark, fabricators wrapped the 7-foot figures in neon. To fill in the background, Star Signs fabricated the 10-by-20-foot bandshell from aluminum and added PVC overlays for dimension. The bandshell also features corona rays made of steel I-beams with neon. These serve a structural as well as aesthetic purpose by supporting the entire element.

To round out the building’s main identification, Star Signs installed stainless-steel channel letters to spell out "The Museums at 18th and Vine" above the doors. At the left, channel letters mark the Jazz Museum; at the right, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

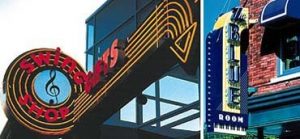

Star Signs’ next task was fabricating the exterior signage for the Jazz Museum’s Swing Shop. In keeping with the neon theme, the shop fabricated a round, projecting, two-sided aluminum sign, 6 feet in diameter, with aluminum trim-cap channel letters wrapped around a treble clef. The clef is flat-cut aluminum mounted over an internally illuminated, frosted-acrylic disk. Beneath this signature sign runs a horizontal band of border tubing mounted on a steel beam. The word "Gifts," and yellow neon lights culminate in an arrow pointing toward the door.

The final piece of exterior signage contributed by Kiku Obata identifies the museum’s Blue Room, a space that showcases exhibits by day and, four nights a week, turns into a nightclub. Measuring 4 by 11 feet, this aluminum sign, painted blue and shaped like a piano, projects vertically from the building.

According to Mike Vickers of Star Signs, the nomenclature for "The Blue Room" combines reverse-channel aluminum letters, open-channel letters and routed aluminum. Triple-stroke, blue-and-white neon, fluorescent backlighting and a white-neon border add a buzz. The word "Blue" is mounted to a raised aluminum panel with three colors of gold painted stripes. The piano keyboard features fabricated plastic with cut-out and applied dimensional piano keys. After dark, the keys light up. Thin, 1/4-inch aluminum rods resembling piano wire continue the theme. To accentuate the dynamic of the sign, a series of chase bulbs are affixed to the outside of the cabinet.

Giving Shape to Jazz

Boston’s Amaze Design, which specializes in aquariums, museums and zoos, created the interior exhibits. According to Project Manager Jeff Fornuto, the company’s designers immersed themselves in jazz culture. They attended weekly classes to learn about the origin and structure of the musical form and conducted focus groups with jazz musicians, including such heavyweights as drummer Max Roach and saxophonist Jackie McLean. These sessions enabled the designers to create exhibits that were mimetic of the nature of jazz.

"The design was developed as a reflection of the art of jazz, as opposed to a more traditional approach," says Fornuto. "The sculptural shapes and forms are evocative of the rhythmic variations of the music. Much of the graphic design came out of the influence of jazz-album cover art in the 50s and 60s."

As a result of this approach, the museum interiors are at once nostalgic and contemporary. Like the exterior signage, the exhibits inside the space are bright and vivid, yet sophisticated. The palette of materials and processes varies in each of the seven major gallery areas.

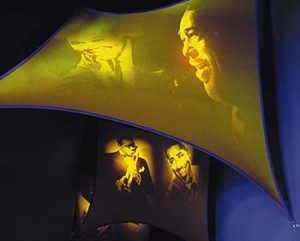

To draw crowds from the lobby of the Horace Peterson Visitor Center into the jazz exhibits, Amaze created a series of Lycra scrims shaped to mimic the curved architecture present throughout the museum. The first and largest scrim features the projected image of Duke Ellington, while smaller scrims, framing the faces of Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, overlap with each other.

Once inside the exhibit area, the storyline is non-linear, which opens up the space and allows visitors more mobility, just as jazz allows improvisation. The exhibits mesh both traditional exhibits and high-tech interactive galleries that allow the curious to explore the complexities of this music and how it’s made.

To achieve this fusion, Amaze contracted with Explus Inc., Dulles, VA. The company fabricated much of the signage and outsourced some tasks to specialty artists.

The more traditional historic exhibits include "Masters Cases" dedicated to jazz titans like Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald. The Parker display, for example, is marked by a large monument sign. According to Dave Dwyer, Explus’ manager of business development, the monument was imaged using Scotchprint

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

Avery Dennison Adopts Mimaki Printer for Traffic Sign Print System

Fiery Releases SignLab 11

21 Larry Albright Plasma Globes, Crackle Tubes and More

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Signs of the Times magazine's news bulletin.

Most Popular

-

Tip Sheet2 days ago

Tip Sheet2 days agoAlways Brand Yourself and Wear Fewer Hats — Two of April’s Sign Tips

-

Business Management1 week ago

Business Management1 week agoWhen Should Sign Companies Hire Salespeople or Fire Customers?

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs Award Winners Excel in Diverse Roles

-

Real Deal3 days ago

Real Deal3 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Editor's Note1 week ago

Editor's Note1 week agoWhy We Still Need the Women in Signs Award

-

Maggie Harlow2 weeks ago

Maggie Harlow2 weeks agoThe Surprising Value Complaints Bring to Your Sign Company

-

Line Time2 weeks ago

Line Time2 weeks agoOne Less Thing to Do for Sign Customers

-

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week agoADA Signs and More Uses for Engraving Machines