Twenty-three years ago, when I worked for a fleet-graphics screenprinter, my training included production art, screenmaking, printing and die cutting. After my indoctrination, I reasonably understood the screen process.

To truly learn screenprinting, I recommend the Screen Print Technical Foundation (SPTF) workshop, "Screen Making: Basic To Professional." At $900 for non-SGIA members, this intensive, one-week course provides a good mix of theory and plenty of hands-on experience.

In addition, I recommend routinely reading ST‘s sister magazine, Screen Printing, and the SGIA Journal, the industry’s two best publications. I also recommend reading Albert Kosloff’s Screen Printing Techniques and Samuel B. Hoff’s Screen Printing: A Contemporary Approach (both available from ST Books, www.stmediagroup.com/stbooks).

Educational videos also justify the investment. Lawson Screen Products’ website (www.lawsonsp.com) offers numerous screenprinting books and videos. Further web resources include www.screenprinters.net/ articles and www.screenweb.com.

The subject of screenprinting often elicits strange looks from signmakers. Sure, screenprinting can be messy and — with solvent-based vinyl inks — stinky. Plus, it involves hazardous materials, and expensive and expansive equipment. So why do it?

Although computer-cut and digitally printed vinyl graphics have increased, screenprinting still offers several advantages for numerous applications, including vehicle markings, window and wall graphics, safety decals and gasoline-pump markings.

For high-volume jobs, screenprinting provides significant economies — more durability than digitally printed graphics and less need for overlaminates. Screenprinting also provides closer color matches and richer colors.

For a small signshop, screenprinting can generate high-volume and profitable work, including vehicle graphics, window decals, bumper stickers, POP signage, safety labels, OEM-identification materials and election signage. Screenprinting is typically faster, and offers lower material costs and better durability, than other vinyl-graphics methods.

Multi-million-dollar companies print most major, vinyl-graphics programs, but novice shops can still handle many jobs via simple printing units with minimal financial risks.

The screening process is simple, but printing onto vinyl involves complex chemistry. The vinyl, ink, clearcoat and application tape must be compatible to produce a durable, problem-free product. Strict adherence to manufacturers’ recommendations and time-tested practices helps minimize mistakes.

The fundamentals

Screenprinting, a form of stencil printing, dates back to ancient times. Now more sophisticated, its basics haven’t changed. Ink is still forced through patterned fabric onto a substrate. Ink passes through the patterns’ open areas onto the screen. Conversely, the patterns’ resistant areas block or prevent ink passage.

The screen fabric is stretched over either wood or metal frames. The frame supports the fabric and serves as an ink reservoir. During printing, ink is poured across the frame’s top edge.

A rubber or plastic tool, called a squeegee, traverses the screen and covers the pattern with ink during the initial flood stroke, or fill pass. A second squeegee pass, called the printing stroke, or impression pass, forces the ink through the screen onto the printing surface.

Originally, the fabric was silk; people called it "silkscreen printing." Today, printers use nylon, polyester and steel fabric.

Patterns can be created several different ways, but fleet-graphics printers generally use the photographic or direct method, in which the screen is coated with photo emulsion. After the emulsion dries, a film positive is placed atop the coated fabric and exposed to a strong, ultraviolet light source. The unexposed emulsion is then washed from the screen, leaving a stencil.

Alternately, the screen stencil can be created using a hand- or plotter-cut stencil film, which is directly adhered to the fabric.

Getting started

The screenprint process usually begins with a sales interview that outlines your customer’s needs. For building- and fleet-graphics programs, this typically involves a site survey or vehicle inspection. Take plenty of photographs and make detailed drawings with measurements. If you’re quoting an existing program, get decal samples.

The quote request must include the specifics about a decal’s finished size, quantity, base substrate, colors and finished cut. Is the decal premasked and clearcoated? Does it require an overlaminate? Determine the project’s artwork format, any special packaging requirements and whether sections of the graphic can be run simultaneously or ganged with other pieces.

For a new or modified design, specify the company’s corporate colors (PMS numbers, color swatches). What does a client like/dislike about an existing design? What logos, brand names and slogans should be incorporated? What colors, if any, can’t be used? For truck and building graphics, what is the design’s "live area"?

A typical production order lists the quantity of decals; material required (vinyl product code); sheet size; decals per sheet; finishing requirements; artwork requirements; and whether special color matching, clearcoating, premasking or an overlaminate is necessary.

The production order helps organize shop time and raw-materials orders. Jobs can be completed on time without disrupting other in-house projects. Better production planning should also lead to better purchasing. Combining purchases fosters quantity discounts.

Following job completion, the production order, combined with the estimate, can evaluate the job. Often, estimates don’t reflect production realities.

Film positives and halftones

Screenprinting is characterized by options. Film positives can be hand-cut, computer-cut and produced photographically. Commercial shops typically use film positives.

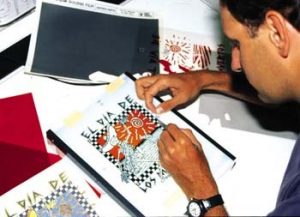

Traditionally, highly skilled craftsmen hand-cut these films. Subsequently, screenprinters adopted many photographic techniques used in offset lithography. Today, computers generate designs, making screenprinting much easier for signmakers.

The simplest film positive is hand-cut Rubylith

Business Management1 week ago

Business Management1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

True Tales2 weeks ago

True Tales2 weeks ago

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks ago

Editor's Note5 days ago

Editor's Note5 days ago

Maggie Harlow2 weeks ago

Maggie Harlow2 weeks ago

Line Time1 week ago

Line Time1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology6 days ago

Product Buying + Technology6 days ago