When I entered the sign business in the mid-1970s, industry technology had evolved little from the days of medieval guilds. As a designer and patternmaker, I turned out many hand renderings and used the available primitive machines to prepare art for production. I relied primarily on a circa-1950, hooded device known by the old-timers as a “Lucy.” Its hand cranks controlled a bellowed lens, which projected, enlarged or reduced art onto a glass screen for tracing.

The completed art, usually prepared in ½-, 5/8- or ¾-in. to 1-ft. scale, was brought into a darkroom and placed in an overhead projector for projection onto 4-ft.-wide rolls of gridded, brown pattern paper. I traced the projection with an ultra-bright, electric-arc carbon pencil, which burned holes into pattern paper for pouncing by hand with a chalk or charcoal pounce bag.

Logos or type required printing black-and-white “photostats,” which were typically secured with rubber cement onto high-grade posterboard. Or, with a very steady hand, I used an X-Acto swivel knife to cut images out of red film on an acetate backer, known as Rubylith®. Without computer imagery, meticulous, mechanical work was required for photographic reproduction.

In 1983, Gerber Scientific Products’ Signmaker, despite its crude, one-line, red-pixel readout, ushered in design mechanization. Now, more than a quarter-century and thousands of technological advancements later, ARTfx, like most other signshops, employs such sophisticated programs as CorelDraw® and Adobe Illustrator® and PhotoShop®. But, unlike most others, our conceptual work is still born at the end of a pencil.

I believe hand rendering still provides many design positives, and that computer renderings ultimately benefit when preceded by doodles. Ideas emerge instantly in a stream of consciousness, where fluidity may suffer during the mechanical process of clicking a computer mouse.

Conversely, hand renderings past the initial idea stage hinder progress. Gears must shift, and CAS designs must proceed quickly. When clients so dictate, software enables swift changes in colors, dimension, shape, etc. Images can be filed and stored for records, conversion or production. In design’s latter phases, the guy working with a pencil may waste hours.

Advertisement

CorelDraw offers sign-design flexibility because it very intuitively produces shapes, fills and shadows. Adobe programs have proven advantageous for composing type because they feature quick editing and rapid letter refinements. CorelDraw tends to be cumbersome when fine-tuning type. Photoshop offers terrific in-situ renderings; there’s no better way to superimpose a design on its planned environment.

We operate our plotters and routers with Gerber’s Graphix Advantage. We have Gerber’s Omega™ software, but our veteran production staff has resisted the changeover. Gerber software creates art files that are production-grade, but, in our experience, doesn’t provide the flexibility in producing time-effective or efficient presentations.

Once we’ve secured approval, the art requires clean-up to ensure all shapes and converted fonts maintain straight lines and smooth curves when adapted to full-size scale. After using CorelDraw and Adobe Illustrator to reduce the file to its basic shapes and types, we use Gerber’s Composer software to enlarge the file to full size and correct any erratic shapes.

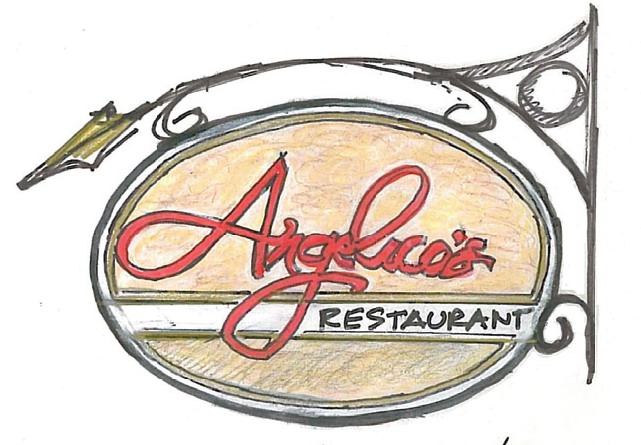

The subsequent photos underscore my design process. Hand renderings have been interpreted by designers using CAD software. Using this tandem approach, I believe the traditional design fundamentals I learned, when merged with current technological amenities, optimizes design aesthetics and efficiency and creates the best possible final product.

Lawrin D. Rosen is the founder of Bloomfield, CT-based ARTfx Signs.

Tip Sheet2 days ago

Tip Sheet2 days ago

Business Management1 week ago

Business Management1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago

Real Deal3 days ago

Real Deal3 days ago

Editor's Note7 days ago

Editor's Note7 days ago

Maggie Harlow2 weeks ago

Maggie Harlow2 weeks ago

Line Time1 week ago

Line Time1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago