When someone says nose art,” the term conjures up images of World War II fighter planes careening through the sky combating the Luftwaffe while sporting pin-up girls, predatory eagles or “Old Glory” — and, in some cases, all of the above.

Nose art is a vital part of military aviation history that enriches the mythology of vintage bomber planes and other military aircraft. However, nose art is still alive and well, as evidenced by the handiwork of Steve Barba of Sturgis Signworks (Sturgis, SD) and Dru Blair of Blair Art Studios (Raleigh, NC).

Nose Art 101

A self-confessed WW II aircraft fanatic, Barba says that even as a child he admired military-aircraft nose art. However, he admits he never thought the art form would be reborn, let alone that he would someday decorate the planes.

He earned his chance at his dream gig through “self-made luck.” He’d been airbrushing and hand-lettering for approximately six years when he learned that the nose artist at South Dakota’s Ellsworth AFB had moved to California. Eager for his opportunity, Barba showed his portfolio to the base’s flight chief. The officer agreed to let him airbrush the next jet.

Barba surmised that the opportunity to embellish even one plane would provide substantial bragging rights. He adds with pride, “The first job must have turned out well, because seven years and 28 jets later, I’m still doing them.”

Barba notes that there are restrictive criteria for applying nose art to military jets. Only four types of aircraft are eligible: the B-1, B-52, KC-135, and C-130.

When a design is finalized, Barba submits it to the flight chief, who’s typically a tech sergeant. After his thumbs-up, it must proceed through the chain of command until it reaches the base commander, who confers final approval.

According to Barba, the military enforces a “3-ft. square rule,” a policy that dictates that nose-art dimensions may not exceed a 3-ft.-sq. area. Because there are no graphic limitations except size, he emphasizes graphics over lettering.

Barba quickly learned that, rather than depict an entire subject, he should emphasize a portion to make it appear larger. For instance, painting an entire tiger on a window would make it appear tiny, whereas painting only the head would make it appear larger.

A crew chief chooses the nose art for his or her jet. Theme restrictions can either limit or spark an artist’s imagination. As an example, Barba cites submitted his design for Aircraft 99, aka “Haulin’ Ass.” He submitted his design to the Flight Chief Rob “Ug” Lee, with a lengthy explanation about its meaning. Gold miners in South Dakota’s Black Hills region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries used donkeys (or asses) for hauling supplies, while dynamite symbolizes the aircraft’s artillery accurately hitting its targets.

Killer arachnid

When he originally finished the design for the Air Force’s “Black Widow,” Barba submitted it to the Letterville Bull Board Website for feedback and possible enhancements from fellow Letterheads. The approximately eight to 10 designs he received in response all pointed him in the right direction — he incorporated elements from everyone who offered suggestions. He credits John Deaton of Deaton Design (Harlan, KY) with streamlining myriad elements and techniques into the design that Barba ultimately used to decorate the plane.

To begin the process, he gridded a loose square on the pilot’s (left) side with a yardstick, between the side window and the defensive system operator’s (DSO) porthole window on the right-hand side. He used a panel line approximately 27 inches below the nose art to measure straight lines. After the grid was made, Barba freehanded the design, a process that could occupy 10 minutes to an hour, depending on complexity.

“Black Widow” took approximately 20 minutes, because he wasn’t familiar with the letter style, Mirage Bold. With a Mack 1-in. flat brush, he applied 1Shot™ bright red, mixed with a gloss modifier. Barba highlighted the red and shaded it into a ball shape, then airbrushed shadows for the legs and body.

When airbrushing airplanes, Barba uses the Paasche Millennium model because of its narrow head and comfortable feel.

He painted the spider’s body and legs with 1Shot black and a #12 quill — a large quill that holds ample paint. When designing “Black Widow,” Barba painted the webs different sizes for a more natural look. Further, he avoided symmetry to create a more “animated” look.

Barba airbrushed white highlights and an orange fade to the webs. For heightened detail, Barba added a black outline added with a #6 quill.

The Blair nose project

A native of Columbia, SC, Blair cultivated an interest in aviation art from “the almost universal affinity boys have for cars, planes and anything that goes fast.” His admiration for men and women in uniform also kindled an affinity for decorating military aircraft.

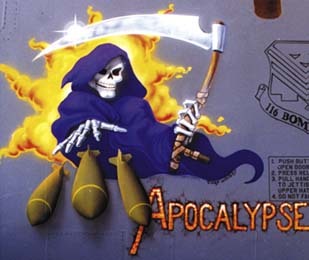

Blair’s portfolio includes airbrushed depictions of an Apache Longbow helicopter, a B-2 Stealth bomber and a SR-71 Blackbird fighter plane. He has also adorned B-1 bombers with his nose art. Blair believes that the B-1 “embodies the essence of global power, brute force and graceful lines.”

One of his more recent B-1 projects was a rendition of George Petty’s painting portraying the legendary “Memphis Belle,” a WW II-era bomber plane featuring a scantily clad bathing beauty. Blair completed the work last spring at Robins AFB in Warner Robins, GA for the 116th Bomber Wing. To accurately reprise the plane’s authentic nose art, Blair studied photos of the original painting and “tried to interpret what I believed to be the artwork’s original intent.”

Blair used automotive paint on the aircraft because of its consistency and durability. The graphic is situated on the plane’s left underside, not directly on its nose, and thus isn’t subjected to the beating associated with moving at high-speed, high-altitude flight.

His tools for the project included the Paasche VL-3 and Iwata Eclipse airbrushes because of their speed, comfort and efficiency. Working in warm weather, he painted the plane as it sat in a hangar, lest the surface become too hot.

When painting a gargantuan aircraft such as a B-1, Blair notes that all details must be emulated to a grand scale so they can be viewed several thousand feet below. Thus, he painted the colors to appear thicker to enhance their detail.

Tip Sheet3 days ago

Tip Sheet3 days ago

Business Management1 week ago

Business Management1 week ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Real Deal4 days ago

Real Deal4 days ago

Editor's Note1 week ago

Editor's Note1 week ago

Line Time2 weeks ago

Line Time2 weeks ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Product Buying + Technology1 week ago

Women in Signs4 days ago

Women in Signs4 days ago