3 Amazing American Sign Museum Restorations

Relighting a classic, reusing arena letters and rediscovering opal glass signs.

Published

7 months agoon

WHEN IT COMES to sheer diversity and richness of the medium, nowhere in the country do signs abound more than at the American Museum (ASM) in Cincinnati. The museum, a time machine of a sort, guides visitors backward and forward to witness the evolution of signage for more than a century. This commitment to documenting the sign industry entails a wealth of historic signs in the museum’s ever-growing collection.

In recent years the museum has undertaken three notable restoration projects — one of which involves the rediscovery of a nearly forgotten signmaking technique — that give rare and antique signs another shot at glory.

STARRING ROLE

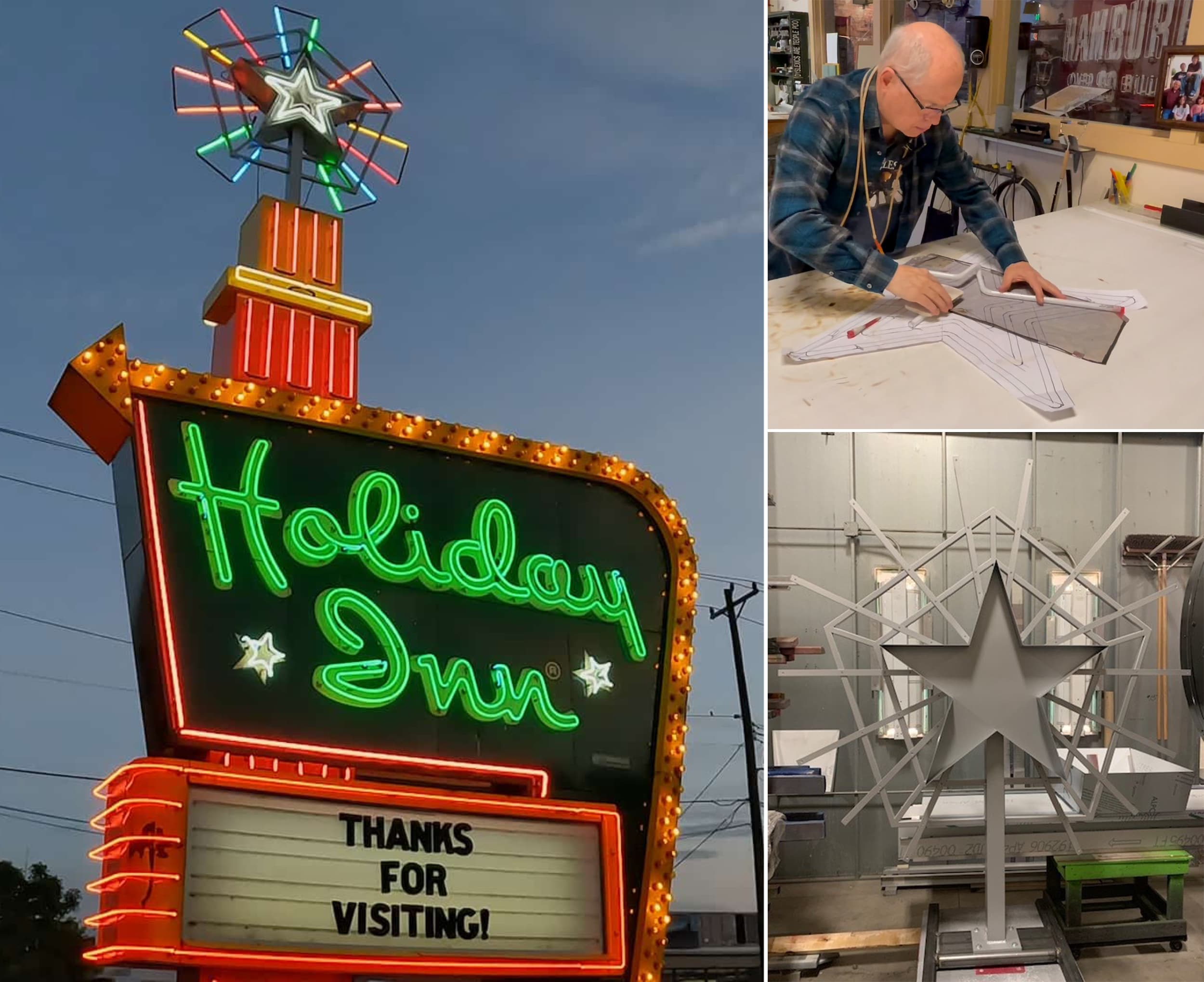

A Holiday Inn “Great Sign” now stands in the parking lot outside the ASM, welcoming visitors in all of its neon and starshine brilliance. The museum acquired the sign from the Young Electric Sign Co. (YESCO) of Las Vegas in 2002, but it arrived in need of repair with, crucially, the tower lined with vertical neon stripes and famous starburst topper section missing. Thus began a restoration effort that involved several companies, dozens of individuals and up to two years of work before the sign could shine again.

ASM Founder Tod Swormstedt has long dreamed of restoring the Great Sign, which stands alongside the Speedee McDonald’s golden arch and the Howard Johnson’s sign as a landmark of the road trip, and an icon of 1950’s America. To kick the process into gear, he contacted longtime ASM supporter Allen Industries (Toledo, OH).

“Tod wanted us to complete the sign and put it back to its original configuration,” says Executive Vice President John Allen of Allen Industries. “He knew that our fabrication department had the capability to manufacture something like this.”

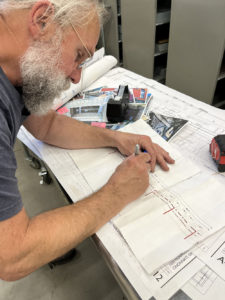

SHAPING STARS: The fully restored Holiday Inn “Great Sign” (left); designing the starburst topper section (top right); the fabricated star cabinet (bottom right).

SHAPING STARS: The fully restored Holiday Inn “Great Sign” (left); designing the starburst topper section (top right); the fabricated star cabinet (bottom right).

The design phase was the most time-consuming, according to Allen. The company’s in-house design department retrieved the 1950’s Holiday Inn sign design by Cummings & Co., the original Great Sign manufacturer, from the museum archives and developed their new designs accordingly. The original schemes were intended for a larger size, which Allen had to scale down to fit the ASM’s version. The designers went back and forth to ensure that every piece would fit properly and that the dimensions were correct, Allen adds.

Allen Industries coordinated designs with Neonworks of Cincinnati, an independent neon workshop co-located inside the ASM, in terms of neon and lighting for the sign. While design was ongoing, Mike Conway, executive president of business development & acquisition at Pyramid Global Hospitality and former Holiday Inn executive, directed a fundraising campaign for the commission of a new star topper. All in all, the preparation drove the entire restoration process, from start to finish, to one and a half or two years. However, fabrication and installation only took three weeks.

Allen fabricated the metal cabinets for the neon-studded pedestal of the 9-ft. topper section from automated grade aluminum panels, in addition to a couple of metal panels missing from the original sign. The resulting colors did not closely match those of the existing sign, but it was not a major challenge for the company. In the meantime, Neonworks improvised the new neon tubing using old photos and videos found online, with additional guidance from Conway, then installed the neon along with the transformers and wiring.

Swormstedt directly contacted Atlantic Sign Co. (Cincinnati) for installation, says General Manager Jesse Cassedy of Atlantic. The company assembled the parts that Allen and Neonworks had fabricated, then used two Wilkie 72Rs to set the steel support and the star topper. “Everything went really smooth; there were no issues at all,” Cassedy says.

Now, the completely restored Great Sign is shining again outside the museum, like a beacon of the past, to visitors and travelers from afar.

LOCAL FACES: Signs for local businesses and regional chains adorn the steel frames below the letters.

LOCAL FACES: Signs for local businesses and regional chains adorn the steel frames below the letters.

GARDEN VARIETY

From its opening in 1949 to eventual demolition in 2018, Cincinnati Gardens indoor arena was one of the city’s foremost sporting and cultural fixtures. It saw performances by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Elvis Presley, as well as hosted hockey and basketball games, professional wrestling matches, stage shows and even political rallies.

After acquiring the “CINCINNATI GARDENS” white channel letters adorning the arena’s façade, Swormstedt and the ASM devised a new use for them as “CINCINNATI Sign GARDEN,” a massive sign mounted on steel frames to the museum’s wall facing Monmouth Street. Swormstedt contacted President Vince Klusty of Klusty Sign Associates Inc. (Cincinnati), who has donated a few signs to the museum and worked on collaborative projects with them over the past couple of years, to help install the letters. For this project, part of the time and labor that Klusty and his team expended was also a museum donation.

When the time for installation came, Klusty recalls a unique attachment method devised by Dave Warner of CW Steel (Loveland, OH). Described by Swormstedt as an incredible self-taught engineer, Warner designed several sign brackets to mount the reverse channel letters to a grid of 4-in. steel tubes. With this method, they were able to develop more effective strategies for each letter whether straight or curved.

The team mechanically fashioned everything the old-fashioned way, using drills, stainless screws, 40-ft. truck baskets and a lift. The porcelain patina letters were in their natural state and did not pose any issue to the three-people installation crew, who finished the job over two eight-hour days.

The letters are not the only component on display, however. Right underneath “Cincinnati Sign Garden,” one the left-hand side, is a set of bas-reliefs sculpted into metal panels depicting the sports that once claimed fame at the Cincinnati Gardens arena — hockey, boxing and basketball. On the right-hand side, an array of signs celebrating local businesses and regional chains — Frisch’s Big Boy, Graeter’s, Turfway Park and more — run for the whole length of the metal structure. It is a sign garden of Cincinnati in the truest form.

RAISING GLASS: Brad Smith has restored the opal glass letters for several of the museum’s signs, including Endicott-Johnson, Stuertz Drugs and G&J Tires.

RAISING GLASS: Brad Smith has restored the opal glass letters for several of the museum’s signs, including Endicott-Johnson, Stuertz Drugs and G&J Tires.

SEEKER OF A LOST ART

With the aid of good fortune, $50 and a box of donuts, in 1980 Brad Smith rescued an opal glass sign manufactured by Flexlume Sign Co. from a railroad station scheduled for demolition in downtown Buffalo, NY. Then Flexlume owner Paddy Rowell, Sr. informed him that glass letters had not been produced for decades and that replacements were practically unavailable anywhere. Thus, Smith embarked on a quest to learn the secrets of opal glass letters — “but life intervened,” he says — until 35 years later.

Smith arrived at where he is now only after a long learning process. Following experiments with different techniques, he discovered that the trick to making a good raised glass letter is through a sharp definition between the flat glass panel and the raised part. “Simply slumping glass over a mold does not yield acceptable results. The sloped base of the letter doesn’t allow the letter to be seated in the cutout cleanly and firmly,” he explains. When he attempted to slump glass into a hollow negative mold, the process produced the desired crisp edge but not the fire polish seen in the original letters.

Then, came a breakthrough — from the internet, where Smith found the original Flexlume patent application that describes the process for forming opal glass under a vacuum. In early 2021, thanks to combination of “luck, connections and being in the right place at the right time,” he managed to purchase the remaining inventory of about 4,500 NOS opal glass letters, as well as six tons of original cast iron molds used in the production of the letters, from the estate of Rowell Jr.

The collection enabled Smith to modify a kiln and fabricate a vacuum system, restoring a letter production process from more than a century ago. “If I don’t have an existing letter or an existing mold, I can fabricate letters from scratch,” he says. Smith prefers to create letters for Flexlume signs, and has a “competitor” in Minnesota with whom he has become good virtual friends and to whom he sends non-Flexlume sign requests. However, he also accepts off-brand letters for collectors.

In the beginning, hoping to restore the Flexlume railroad station sign, Smith approached Swormstedt about the knowledge of making opal glass letters. “He had little to offer … but was very interested to find that I was attempting to learn the process because he had many signs of his own that he would like to get letters for,” Smith recalls.

Now, Smith has replaced the letters in four signs for the ASM: Stuertz Drugs, Endicott-Johnson, G&J Tires and Concord Electric. Swormstedt has been his biggest supporter, providing encouragement, information, resources and connections, he says.

The Rowell estate recently donated a trove of technical and historical documents from the Flexlume archives to the museum, to which Smith has full unrestricted access. He reckons that these resources will soon become publicly available through the museum’s research library.

“I think the ASM is an incredible operation!” Smith says. “In terms of technical resources and historic knowledge, I don’t think there is a better collection in the country and beyond that, the place is just plain fun! You don’t have to be a sign lover to enjoy the museum in all its colorful glory!”

PHOTO GALLERY (14 IMAGES)

Advertisement

Mildred Nguyen is assistant editor with Signs of the Times. A journalism graduate from Northern Kentucky University, she can't focus well if she's not multitasking in some way.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

PRINTING United Alliance Forms Strategic Partnership with ASI

The Joy of Working

5 Signs That Embody Care and Gratitude

Subscribe

Bulletins

Get the most important news and business ideas from Signs of the Times magazine's news bulletin.

Most Popular

-

Photo Gallery1 week ago

Photo Gallery1 week ago30 Snapshots of the 2024 ISA Sign Expo

-

Ask Signs of the Times2 weeks ago

Ask Signs of the Times2 weeks agoWhy Are Signs from Canva so Overloaded and Similar?

-

Paula Fargo6 days ago

Paula Fargo6 days ago5 Reasons to Sell a Sign Company Plus 6 Options

-

Real Deal3 days ago

Real Deal3 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Benchmarks2 weeks ago

Benchmarks2 weeks ago6 Sports Venue Signs Deserving a Standing Ovation

-

Photo Gallery6 days ago

Photo Gallery6 days ago21 Larry Albright Plasma Globes, Crackle Tubes and More

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs: Brandi Pulliam Blanton

-

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago2024 Women in Signs: Alicia Brothers