Darek Johnson is ST’s Senior Technical Editor/Analyst. You can email him at darek.johnson@stmediagroup.com.

Children, especially small children, are, for whatever reason, often sticky and unpleasant to touch. Dogs are different. A dog, if sticky, will spend the day licking the stickiness away. Because of this trait, I habitually pat dogs, but not children.

It’s not that I don’t like kids — indeed, my friends who have them will say I’m friendly and interested in their progeny — if the darlings are washed, calm and well mannered.

Imagine, then, my unease when I discovered my out-bound, Delta flight from Orlando (and ISA’s Sign Expo 2010) was filled with child-burdened families returning home from their Disney World vacations. My overall recollection, today, is of a plane full of children — or was it monkeys? — dressed by garanimals.com.

I had wanted a quiet flight, so I could read a book and perhaps doze.

My luck. A young woman carrying an infant arrived at my aisle and sat next to me. Once seated, she balanced the baby on her lap. It screeched and moved constantly, as if motorized.

Also, they both, then, smelled of Johnson’s baby powder.

Once airborne, the overall scene worsened. Across the aisle — beneath bright, reading lights — parents applauded a three-year old who sang and toe-danced across their folded down, seat-back trays.

Behind me, young Tyler — “Put your hand over your mouth, Tyler.” — sniffled and sneezed, which, of course, I’m doing now.

Thank you, Tyler.

Too soon, the next-seat infant crafted a keen odor that, oddly, the mother didn’t seem to notice.

I leaned into the aisle way, longed for fresh air, earphones and a Stevie Nick’s album.

Amazingly, all the parents and grandparents sat placidly amid this messy swarm, as if everything was normal.

I survived, obviously, but I’m now convinced that airplanes — especially outbound Orlando airplanes — should provide daycare zones that are equipped with high-security doors.

Or parachutes.

Advertisement

Race-car builder Ron Dennis, in the March issue of Car and Driver, tells of a 1988 telephone call from a Marlboro executive — Marlboro was the team’s chief sponsor — who said “it would be in the interest of the sport” if Team McLaren started to lose races.

Dennis began his racing career at age 18, as a Cooper Racing Car Co. mechanic; two years later, he became its chief mechanic; in another four years, he initiated his own race team.

From day one, Dennis said he thought that winning races was doing the job. This philosophy obviously led to his response to the Marlboro executive’s request: “Yeah, like that’s gonna happen.”

Success, I think, is always more contingent upon attitude — as Dennis’ remark expressed — than skill or education.

Frederick R. Brooks Jr. recently published The Design of Design, in which he discusses today’s trend of separating designers from implementation and the end user. Brooks describes this trend as the “divorce of design for use and implementation.”

Brooks is Kenan professor of science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He was instrumental in IBM’s early computer developments and received the National Medal of Technology Award in 1985.

In his book, he said people seldom home-build professions today, then noted how such successful entrepreneurs as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and the Wright Brothers had fabricated working versions of their inventions. He further explained that today’s separation of designer and manufacturer is necessary because vast technologies demand specialization and consequently, more participation from professionals.

However, he also observed, and complained, that modern technology applications seldom receive practical-manufacturing (hands-on) oversight. This loss of contact causes manufacturing problems, he said, because communications between people is always less effective than communications within a person.

His viewpoint also applies to politicians who lack business experience, but make critical decisions that affect the small-business community. Hands-on people are more inclined to cut through political and technical sludge.

In real life, product designers who help build, install and maintain their devices consistently design more functional (and better) ones, as do sign designers who have fabrication and installation experience.

A few years back, I attended an event at a digital-print company’s chief engineers’ home and soon discovered a British sports car in his garage, which he was rebuilding. I once amateur raced such cars, so we enthusiastically looked over the car and discussed its idiosyncrasies.

I learned that several other of the company’s engineers were restoring old cars; one had built a Cobra kit car.

Their wrenching experience showed up in the firm s machines. The devices were effective, strong, useful and practical to maintain.

Brooks said people who haven’t performed hands-on work too often make major decisions which cause problems. He illustrated that few naval architects have commanded a ship, much less wielded one in battle.

In 1997, then Ph.D. student Andrew S. Molnar wrote “…rapid changes in many fields are making basic knowledge and skills obsolete, because we are experiencing a scientific information explosion of unprecedented proportions.”

Today’s knowledge base is immense, he said, and explained that modern researchers access thousands of rapidly growing databases millions of times annually.

Molnar said modern education no longer focuses on teaching through lectures and demonstrations; instead, it emphasizes thinking and problem solving skills. Educational emphasis has moved from learning to thinking — and organizing information.

Because we’re educating our children, such as the ones on the airplane, as Molnar described, for a computerized, not mechanical world, they may later quarrel with Brook’s hands-on philosophy.

Thus, I worry about this new education philosophy and the future of blue-collar vocations. Will any of the kids on the airplane want to become sheet-metal benders, welders, sign fabricators — or race car mechanics?

Someone like Ron Dennis?

Dennis joined the then-uncompetitive McLaren team in 1980; in ’81, he and his partners bought out McLaren’s shareholders, and, in 1984, Dennis’ McLaren cars won 12 out of 16 top races.

Today, the race executive’s resume includes running the McLaren racing team (with 20 world championships) and building McLaren Car’s F1 Supercars, a (very) high-performance street car. He now chairs McLaren Automotive and oversees the building of its 600-bhp, MP4-12C Supercar.

Ron Dennis, the mechanic, cut through the sludge.

Photo Gallery2 weeks ago

Photo Gallery2 weeks ago

Paula Fargo2 weeks ago

Paula Fargo2 weeks ago

Real Deal1 week ago

Real Deal1 week ago

Photo Gallery2 weeks ago

Photo Gallery2 weeks ago

Projects1 week ago

Projects1 week ago

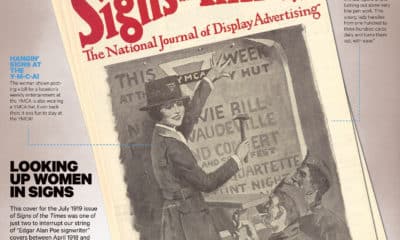

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Signs of the Times2 weeks ago

Signs of the Times2 weeks ago

Business Management7 days ago

Business Management7 days ago