Digital Printing

Prints Aren

Some advice on profiles, JPEGs and raw files

Published

17 years agoon

Ray Kroc, McDonalds® Corp. founder, believed luck was a divi¬dend of sweat. “The more you sweat, the luckier you get,” he’d say. He also fancied Peter Drucker’s principle of working to make a product, not money. To wit, “If you work just for money, you’ll never make it, but if you love what you’re doing and always put the customer first, success will be yours.” Indicative of this attitude, Kroc said he cared about hamburger more than anyone else.

Similarly, dedicated prepress persons care about prepress and its related gadgets more than (almost) anything else, because, like it or not, digital-color printing and its prepress counterpart are a lifestyle, not a job.

The rocket science of digital printing, prepress, color-manage¬ment and application profiles are making more news today than one would expect, and I’m glad to see it, because processing an image for print (prepress) is the most important ingredient in successful color printing.

Prints aren’t burgers

Although endless color-management stories adorn sign and digital-print magazine pages, the writers seldom address failure. Time, unlike overcooked burgers, isn’t cheap, nor are inks and media. Thus, a botched, large-format print can devour a job’s profits, unless failure is built within the price, as it should be.

AdvertisementPrinting luck begins with preparation and planning, which should occur prior to buying a print machine or its accouterments: computers, software and a laminating device. Worsening the matter is interpreting the onslaught of press releases and advertisements that announce printer and software news. Still, sometimes, you’ve got to grab the ring.

Motorhead mindsets

True danger exists in thinking only about machines and not buying new software packages or upgrades. Although shop owners should confer with their design and prepress staffs before purchasing new software, they should also contemplate any design-group aversion to learn new systems. Such reluctance could delay a shop’s overall efforts.

Experienced sign designers should expertly run signmaking software and intimately know such image-editing software as Adobe Photoshop™, Lightroom™ or Corel’s advanced systems. In short, they should have such packages loaded and ready to make image modifications and changes, such as, broadening a color gamut by changing a color space from sRGB to aRGB 1998.

The sRGB color model, designed for transferring color data between unidentified devices, holds the smallest color space defined by RGB color standards. Color enthusiasts convert or apply the Adobe RGB 1998 (aRGB), an expanded color space.

See sRGB as a box of 24 crayons, aRGB as a box of 48.

AdvertisementProfiles

A profile is a color-management-system file that contains data which represents the color characteristics of a particular device, usually a digital printer or monitor. It codes your printer’s systems so they provide the best print colors possible. The International Color Consortium (ICC) identifies ICC Profiles as those conforming to its specifications

Print-machine profiles, those you build in shop or provided by a manufacturer, are crucial to a color-management (and print-production) system. Profiles work best with well-maintained, calibrated, color-management and print-processing systems. Typically, this would include a calibrated monitor, a RIP, color-management software and an image-editing application program such as Photoshop or Corel® Paint Shop Pro® Photo.

Although a print profile enables more accurate colors, it may also allow your printer to produce a wider (printable) color gamut; further, it may improve your print’s gray-tone scale, which adds detail to its highlights and shadows.

Prior to buying a digital printer, determine how you’ll acquire profiles. Currently, you can obtain them from a manufacturer’s website or make your own. I prefer both methods. Some manufacturers’ websites display a profile tag on the first page; other sites make you search, something you’d rather avoid, especially while cranking out a rush job.

There’s a message here, to both web geeks and marketers.

AdvertisementInterpretive color variations exist between printer brands and, surprisingly, identical models. Additionally, a slightly maladjusted printhead (worn shaft bearings) can change print quality and colors; a change in dpi may amend hues and colors; inks and media can (will) vary from batch to batch, and ink may lose intensity if stored too long. Further, installing third-party media or inks trashes a manufacturer’s profile.

Manufacturer-provided profiles can’t integrate such oddities, thus the “roll-your-own” advantage is clear: You can tune a homemade profile to your machine, situation and third-party media. Most importantly, you can create a new profile when you need it. Tuesday at midnight, for example.

Raw, a non-suffix

Raw, the now-popular photography “format,” isn’t really a format — it’s off-the-sensor camera data that are CCD- or CMOS-generated elec¬tronic codes (those representing the image) that exist before a camera’s internal software converts them, usually, to JPEG. Raw images can come from digital cameras, film cameras, existing prints, slides, artwork, or computer-built images.

Photographer/web consultant Elmo Sapwater (www.photo-news.com) says competing camera manufacturers integrate different raw codes into their cameras; thus, you need corresponding software to manipulate raw-image files. Nikon offers its Nikon Capture 4.0; Canon, its RAW Editing Software; and Adobe, its Camera RAW DNG (digital negative) converter and Lightroom. Each modifies the original raw codes upon import and converts them to a proprietary file format you modify.

Elmo also says people wrongly capitalize the word, which, other than in branding, “raw” describes off-the-rack codes; see it like uncooked hamburger meat.

Shooting in raw gives a photographer more final-image choices, but he or she makes those choices later, when computer-processing the image. See this like sprinkling Tabasco sauce on your hamburger patty as it sizzles on the grill.

Designed to work with Photoshop, Lightroom helps you import, manage and present large quantities of digital photographs.

Further, it’s a cool software; the single-page, control-panel screen displays all the software’s editing tools. Surprisingly, you won’t find a Save button in Lightroom; instead, you export the file to your desired designation.

JPEG, the hazardous format

A universally used format, JPEG (created by the Joint Photographic Experts Group) is a file format compatible with web browsers, viewers and both PC- and Mac-based, image-editing software. Most pocket-sized digital cameras automatically convert their raw data to JPEG. To get the best image, Elmo says, select your pocket digital camera’s highest quality JPEG setting (sharpness), if it allows a choice. Older, or less expensive digital cameras won’t have a raw setting; they automatically convert their raw data to JPEG, a compression software.

Compression software comes in two types – lossless, which maintains image integrity, and lossy, which deletes image data and thus lowers the image quality. JPEG is lossy.

Image-editing software, such as Photoshop or Corel Paint Shop Pro Photo, automatically compresses a JPEG file at each file-closing (save); it’s the nature of the beast. Compression reduces an image’s overall file size by diminishing its color and finer details (human vision is less apt to pick up such cutbacks), which lessens the file size, but quickens the transfer and download times.

See JPEG like a cheap hamburger patty, the water-soaked grind that shrinks as you cook it.

Initially, JPEG’s compression causes an unnoticeable loss of image-quality; however, repeated saves chip away at the file size and, in time, significantly abrade the image. To eliminate this hazard when editing a JPEG image, change the format from JPEG to TIFF (by Saving As). If needed, you can re-apply the JPEG format in the final save.

Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) is a lossless format typically applied to high-color depth images. Generally, it’s a good-choice format. It conforms to all popular image-editing softwares and, interestingly, allows 16-bit color channels.

The raw truth

Like finding raw meat on your Wendy’s bun, it’s unlikely your shop will receive a raw file for processing. Still, if you’ve loaded Photoshop (and Lightroom for its file-facilitating features), you can process a raw file. This is better than sending a customer elsewhere. Do you need to use raw for your shop’s photos? No. Not unless you’re a serious photographer. Truth is, we’ve all shot millions of digital images in JPEG format, so, obviously, you can obtain successful images with it.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

Advertisement

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Signsofthetimes Magazine.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Photo Gallery2 weeks ago

Photo Gallery2 weeks ago30 Snapshots of the 2024 ISA Sign Expo

-

Paula Fargo1 week ago

Paula Fargo1 week ago5 Reasons to Sell a Sign Company Plus 6 Options

-

Real Deal7 days ago

Real Deal7 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Photo Gallery1 week ago

Photo Gallery1 week ago21 Larry Albright Plasma Globes, Crackle Tubes and More

-

Projects7 days ago

Projects7 days agoGraphics Turn an Eyesore Cooler Into a Showpiece Promo in Historic Plaza

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs: Alicia Brothers

-

Signs of the Times2 weeks ago

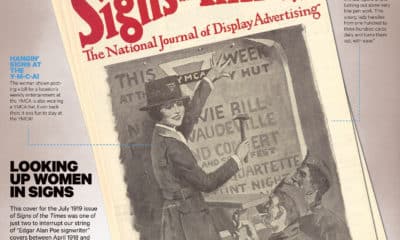

Signs of the Times2 weeks agoJuly 1919 Signs of the Times Cover Features Woman Installer

-

Business Management6 days ago

Business Management6 days ago3 Things Print Pros Must Do to Build Stronger Relationships in the Interiors Market