Digital Printing

Rendering Intent

Seldom-discussed, color-management choices can affect your digital prints.

Published

17 years agoon

Amazing. It’s truly amazing to watch a guy teach high-tech, color-management practices for eight hours and not see him refer to a book or note page, or even to review a fact or two. Not once. But, that’s what Phil Nelson did during X-Rite’s excellent, day-long Picture Perfect Color seminar, held in Cincinnati on July 24.

Phil knows his stuff. His graphic-arts career began in the pre-Mac era of paste-ups and mechanicals, but, during the founding era of computer graphics, he shifted his attention to video animation and produced commercials for ad agencies, HBO and Cinemax. He soon moved to Apple Computers (Cupertino, CA) and, after 10 years, to Adobe Systems Inc. (San Jose, CA), where he promoted its applications to web designers. Seven years after that, he formed Phil Nelson Imaging, a Stamford, CT-based digital-photography agency.

About then, he also began teaching for the Graphics Intelligence Agency (GIA), now X-Rite Color Services (Grand Rapids, MI), and wrote The Photographer’s Guide to Color Management.

In Cincinnati, Phil taught color management and profiles. In the process, he discussed software tools you may have missed or, at least, not thought about carefully. Rendering intents, for example. A selected rendering intent tells the software what to do with out-of-gamut colors, and your rendering-intent choice can affect your output colors.

Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, QuarkXPress and some RIPs let you select rendering intents when performing International Color Consortium (ICC) profile conversions. You may also find different names for rendering intent in these softwares: “intent” or “image intent.” I’ve seen it as “graphic intent” in Illustrator.

Profiles

AdvertisementAn ICC profile is a look-up table (LUT) file, that is, a color map that defines color space properties. Profiles also dictate how a particular device reproduces color on a particular media. Profiles that accurately characterize a particular device – monitor, scanner, digital camera or printer – give you the best color-managed workflow, if, of course, all are calibrated.

Color management requires books to explain. Thus, my discussion here can’t begin to cover the details. Briefly, gamut describes the colors a device can capture, display or output.

ICC profiles, once set, redefine a device’s color gamut. Without a profile, the gamut is a wild card — it can’t define the RGB or CMYK values that make up a color space. For example, in an unmanaged color space, red may be blood red instead of apple red. Correct profiles are the key to a color-managed workflow; they cause an image of a fire-engine red Acura RSX to print as fire-engine red Acura RSX.

Adobe says Photoshop 6. 0 (and later) supports ICC profiles for all display, input and output devices. It says you can embed ICC profiles into RGB, CMYK or grayscale files saved from Photoshop 6.0 or later. An embedded profile remains with the file, so any ICC-aware application can read the device’s color-space information.

Dealing with color gamuts can be difficult, especially when converting a wide-gamut RGB to a printer’s smaller CMYK (RGB devices almost always have a larger gamut than CMYK devices). When converting a larger gamut to a smaller one, you lose the outlying colors; a similar loss occurs when you select lesser color spaces in Photoshop, converting aRGB to sRGB, for example. See it like dropping a handful of multicolored sprinkles onto a doughnut – most fall off the doughnut.

Essentially, but in different ways, your rendering-intent selection compresses outlying colors into the new mix. Thus, the proper rendering intent helps you save those would-be-lost colors. And, although the system is designed to manage out-of-gamut colors, choose your rendering intent carefully — your choice may affect all the files’ colors.

AdvertisementRendering intent choices

The ICC profile specifications list four different rendering intents.

Absolute colorimetric rendering reproduces in-gamut colors exactly, one-to-one. It also reduces out-of-gamut colors to the closest color match, which can negatively affect saturation and lightness.

Absolute colorimetric has other disadvantages: It tries to reproduce the target space white in the source image, which, especially if your final print has a white border, may cause an unwanted tint in the printed image. It doesn’t regard the light source and may also change the relationship between the in- and out-of-gamut colors, which can visually affect the printed image, meaning the colors may not “look right.”

The white point is the color-balance high point. See it like an invisible line passing through a 3-D color gamut, from black (bottom) to white (top). If the line inclines off the white center, towards blue, say, you’ll get a cool white; a red leaning, of course, causes a warm white hue.

By the way, light-cyan and light-magenta inks, added to a print machine’s CMYK system, enables finer tonal gradations in a print’s lighter areas, but don’t enhance a printer’s gamut, as might other ink font additions (orange, green, blue or red, for example).

AdvertisementRelative colorimetric equates to absolute colorimetric. It matches in-gamut colors one to one and trans¬forms out-of-gamut colors to the nearest reproducible hue, but it also sets the white-point compensation by comparing the source color space white point to the destina¬tion color space, and then shifts all colors accordingly. Adobe says to check the Black-Point Compensation box when using relative colorimetric, to preserve color relation¬ships without sacrificing accuracy.

Perceptual rendering attempts to compress the source-space gamut into the target space. In doing so, it may de-saturate all colors (by pushing the out-of-gamut colors into the target gamut), but it also strives to maintain the relationship between the colors, and this helps preserve the image’s overall appearance. Adobe says it’s most suitable for photographic images, because it “aims to preserve the visual relationship between colors in a way that is perceived as natural to the human eye.”

Saturation maps the saturated primary colors in the source space to the saturated primary colors in the target space, without affecting hue, saturation or lightness. Adobe says it aims to create vivid color at the expense of accurate color. It’s designed to use with strong graphics, such as charts and signs.

Black-point compensation

Like Ansel Adam’s Zone System (first devised in 1945), the number of intermediate grays an image contains between the white point (pure white) and the black point (pure black) determines its tonal range. Interestingly, ICC profiles have white-point rules, but none exist for black points. Like white-point matching, black-point matching attempts to translate the source black to the target; it can be good or bad news, because it affects the translation — zones —between the selected color spaces.

When checked, Adobe’s black-point compensation box (in Convert to Profile) forces a black-point compensation that ensures the converted file’s black isn’t reduced. Washed out, that is. Adobe’s general rule is to check the Black-Point Compensation box when you’re converting an image from RGB to CMYK or a CMYK to CMYK profile, but not when you’re converting from one RGB space to another.

Which to choose

The choice isn’t as easy. For example, suppose you’re using Adobe RGB (1998) color space and converting it to CMYK while using a custom profile and the perceptual rendering intent. In most instances, the Adobe RGB gamut is larger than the print machine’s gamut, but, in practice, the image gamut could be the same size as the press gamut; therefore, the compressing action of perceptual rendering intent would eliminate useful color.

Perceptual and relative colorimetric are the most common color-rendering choices, although, Phil says, absolute colorimetric has the least color shift. Relative tends to compress colors onto the gamut edge, thus flattening some colors. Perceptual compresses into the gamut. Saturation, because it ignores hues, can modify subtle colors.

The gurus say to use the intent that provides images you like. Most add that Perceptual is best for natural images, while Relative is best for vector art, but it doesn’t have to be this way. For example, many photographic images, especially lighter ones, fare better under relative, because perceptual may apply unnecessary gamut compres¬sion. A general usage rule says to use the perceptual rendering intent when converting from an RGB color space to a CMYK color space, and relative colorimetric when converting from RGB to RGB or CMYK to CMYK color spaces.

One precautionary measure is to toggle the “Convert to Profile” box Preview button on and off as you select different intents (and the black-point setting), and check the onscreen image for changes and banding. Another is to make test prints. Choose the setting that provides the least amount of image change and doesn’t introduce banding.

Seattle-based Chromix offers its ColorThink 3.0 Pro software that allows you to view your gamuts in 3-D space. Chromix also offers profile-making software. X-Rite offers many color management products, including its ProfileMaker Pro software.

SPONSORED VIDEO

Introducing the Sign Industry Podcast

The Sign Industry Podcast is a platform for every sign person out there — from the old-timers who bent neon and hand-lettered boats to those venturing into new technologies — we want to get their stories out for everyone to hear. Come join us and listen to stories, learn tricks or techniques, and get insights of what’s to come. We are the world’s second oldest profession. The folks who started the world’s oldest profession needed a sign.

You may like

Advertisement

Subscribe

Magazine

Get the most important news

and business ideas from Signsofthetimes Magazine.

Advertisement

Most Popular

-

Photo Gallery1 week ago

Photo Gallery1 week ago30 Snapshots of the 2024 ISA Sign Expo

-

Ask Signs of the Times2 weeks ago

Ask Signs of the Times2 weeks agoWhy Are Signs from Canva so Overloaded and Similar?

-

Paula Fargo1 week ago

Paula Fargo1 week ago5 Reasons to Sell a Sign Company Plus 6 Options

-

Real Deal4 days ago

Real Deal4 days agoA Woman Sign Company Owner Confronts a Sexist Wholesaler

-

Photo Gallery1 week ago

Photo Gallery1 week ago21 Larry Albright Plasma Globes, Crackle Tubes and More

-

Women in Signs2 weeks ago

Women in Signs2 weeks ago2024 Women in Signs: Brandi Pulliam Blanton

-

Women in Signs1 week ago

Women in Signs1 week ago2024 Women in Signs: Alicia Brothers

-

Signs of the Times1 week ago

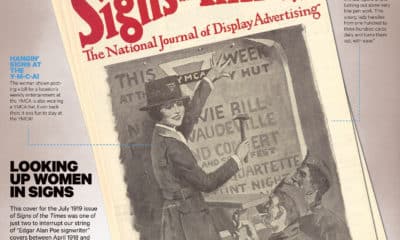

Signs of the Times1 week agoJuly 1919 Signs of the Times Cover Features Woman Installer